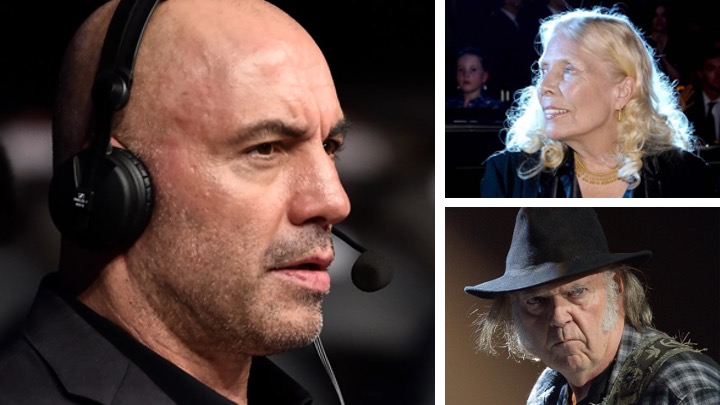

If you don’t know, I’m a musician and off-and-on member of rock bands since 1967, meaning I was influenced socially and politically by the great singer-songwriters of the 60s and early 70s, perhaps none so much as Neil Young and Joni Mitchell. 50 years later, I feel punked because they’re pressuring Spotify to censor Joe Rogan – either his podcast or their play list.

If you don’t know, I spend most of my youth in Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina, where radio stations blared Young’s “Southern Man” and Mitchell’s “The Fiddle and the Drum.” That’s right, two Canadians got rich because their anti-South and anti-USA songs were not banned by adults who disagreed with their views.

Right now, Spotify is sticking with Rogan and dropping the works of the faded rockers, but Substack’s Glenn Greenwald reports the Neil Young spat cost Spotify $4 billion in market value last week, inviting Greenwald to muse, “If liberals succeed in pressing Spotify to abandon their most valuable commodity (Rogan), it will mean nobody is safe from their petty-tyrant tactics.” This is why I publish on Substack – and why I have reprinted the rai·son d’ê·tre article below:

Society Has a Trust Problem. More Censorship Will Only Make it Worse.

Last year, anthropologist Heidi Larson, founder of the Vaccine Confidence Project, said that efforts to silence people who doubt the efficacy of the Covid-19 vaccines won’t get us very far. “If you shut down Facebook tomorrow,” she said, “it’s not going to make this go away. It’ll just move.” Public health solutions, then, would have to come from a different approach. “We don’t have a misinformation problem,” Larson said. “We have a trust problem.”

This point rings true, as we face growing pressure to censor content published on Substack that to some seems dubious or objectionable. Our answer remains the same: we make decisions based on principles not PR, we will defend free expression, and we will stick to our hands-off approach to content moderation, because we believe open discourse is better for writers and better for society.

We allow writers to publish what they want and readers to decide for themselves what to read, even when it means putting up with the presence of writers with whom we strongly disagree. This approach is a necessary precondition for building trust in the information ecosystem as a whole. The more that powerful institutions attempt to control what can and cannot be said in public, the more people there will be who are ready to create alternative narratives about what’s “true.”

Spurred by a belief that there’s a conspiracy to suppress important information, it is clear that these effects are already in full force in society. Trust in social media and traditional media is at 27%, an all-time low. Trust is at 39% in the federal government’s problem-handling and at 33% in America’s major institutions (source: Gallup). The consequences are profound.

Declining trust is both a cause and an effect of polarization, reflecting and giving rise to conditions that further compromise our confidence in each other and in institutions. These effects are especially apparent in our digital gathering places. To remain in favor with your in-group, you must defend your side, even if it means favoring conspiratorial narratives over the pursuit of truth.

In the online Thunderdome, it is imperative that you are not seen to engage with ideas from the wrong group; on the contrary, you are expected to marshall whatever power is at your disposal – be it cultural, political, or technological – to silence their arguments.

In a pernicious cycle, these dynamics in turn give each group license to point to the excesses of the other as further justification for mistrust and misbehavior. It’s always the other side who is deranged, dishonest and dangerous, who shuts down criticism because they know they can’t win the argument, who has no concern for the truth. Thus, each group becomes ever more incensed by the misdeeds of the other and blind to their own. The center does not hold.

Our information systems didn’t create these problems: they accelerate them. Social media platforms amplify contentious content [and] ratchet up the pressure on traditional media to vie for attention at all costs. People fixate on branding their opponents as peddlers of dangerous misinformation, threats to democracy [and] terrorists. All the while, the range of acceptable viewpoints and voices within each group gets ever narrower.

This attention economy generates power from exploiting base impulses and moments of attention, [but] a healthy information economy derives power from the strength and quality of relationships that are built over time (writers and readers not feeling like they’re being cheated, coddled, or condescended to). To put it plainly: censorship of bad ideas makes people less likely, not more likely, to trust good ideas.

Giving power to writers and readers is why Substack writers own and control their relationships with their readers. To paraphrase Barack Obama (someone who ought to know), these people do not look to be ruled. Our promise to writers is that we don’t tell them what to do. Not everyone thinks this is the right approach [and] call for greater intervention, making companies the arbiters of what is true and who can speak. To those who endorse such an approach, we can only ask: How is it going? Is it working yet?

We take a strong stance in defense of free speech because we believe the alternatives are so much worse: censorship to silence certain voices [pushes] them to another place. It doesn’t make the misinformation problem disappear, but it does make the mistrust problem worse.

Trust is built over time [and] can’t be strengthened by turning away from hard conversations. For the media ecosystem, it requires building from a new foundation.

Editor’s note: the article above was written by Substack co-founders Hamish McKenzie, Chris Best and Jairaj Sethi.